- It's not only important for students to make their own personal and creative inferences, but also accurate inferences that the author intended all readers to make. In chapter 5, Beers made the point that there is generally a certain knowledge base that readers need in order draw the same inferences -- cultural and historical knowledge of the text is crucial. In my future classroom, I plan on always spending at least one class period discussing the history of the text before we begin it. This can include the time period it is set in, when it was written, the setting, the background of the author, or the culture. The proper historical knowledge base will ensure that students will infer what was intended.

- Inference requires a certain amount of critical thinking on the reader's part. Employing a Socratic Method style of discussion would really help to get students to explain their own inferences. By questioning, and often opposing, their theories and conclusions, the teacher (and other students) can draw out more explanations and reasoning of their inferences. Continuous "why" questions will help students expand their thinking.

- I also really like the idea of giving students a creative outlet in which to portray their inferences. An assignment that has them creating a new book cover for the text they have read could really help them to visualize what they have read. They should create their cover with someone who has never read the text in mind -- the student will focus on what other people can infer from their cover.

- Since I have a background in film, I always try to create an opportunity to include it in the English classroom. A great way to teach inference is by showing students a clip from the middle of a movie they have never seen. They will have to determine the relationships of the characters, what they are doing, why they are where they are, what they are talking about, etc. Using a film is a great introduction of inference skills before the text is presented. This clip from The Philadelphia Story will not only force the students to infer, but it also shows a young girl making inferences based on what she saw outside her window.

- Showing the trailer to a movie can also get students using their inference skills. They will have to deduce what kind of people the characters are, what they will be dealing with, what the title of the film means, and at the most basic level -- the genre of the movie. This trailer for Bringing Up Baby will provide a wide variety of inferences since the plot of the film is already so zany.

- And finally, I got the idea of showing a funny example of poor inferences from a colleague, Anna (who has some other great ideas to promote inference). She used the classic "Who's on First?" skit with Abbott & Costello. I thought that this Marx Brothers clip, from a similar vein, would also be a fun example for students: Where's the Flash?

This is a blog about books, reading, young adult literature, education, teaching, and learning to teach.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Teaching Inference

After reading some of Kylene Beers' suggestions on how to get students to make inferences while reading I realized that I had never really thought of the concept before! It's something that I, and so many other independent readers, do without even thinking about it. For students who are still dependent readers and need to be taught specific reading skills, inference is very challenging. Like comprehension, inference is something that needs to be taught explicitly. Before having students make independent inferences while reading a text, there are a few different activities that can be done in the classroom to teach inference:

Friday, January 20, 2012

A Super Good Day

|

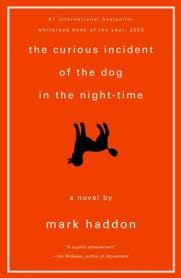

| (A good sign for Christopher, the narrator of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time) |

This rationale sounds exactly like something my nephew, Mikey, would say. Mikey is 7 years old, loves to make graphs on the calculator, his favorite sandwich is a cheese sandwich with shredded cheese (NOT a grilled cheese), is lovingly obsessed with the video game Portal, is a literal genius on the piano, and has Aspberger's Syndrome. He deals with anxiety, sensory overload, and some awkward social interactions. And he's amazing. Maybe I'm biased (I am his aunt and he is my only nephew, after all) but he's pretty much my favorite person. I'm always learning something new from him -- whether it's a fact about the element neon or intuitive insight to his world.

On Wednesday, I was sitting in a 12th grade English class and learned they were about to begin a new book. As I listened to Ms. Roman describe The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon I decided that I would find the time to read it. She explained that the story is told from the point-of-view of a young boy dealing with Asperger's. She shared a list of common symptoms and characteristics that children on the Autistic spectrum deal with and specific Asperger's traits. I sat in the back of the room thinking of Mikey. I borrowed Ms. Roman's personal copy of the book and told her I might be able to finish it over the weekend, since I would be away in Vermont. I returned it to her on Thursday morning.

Throughout exams and study halls on Wednesday I devoured Haddon's novel -- by the time I got home I only had about 30 pages left and finished them quickly. Christopher, the main character, drew me into his world so fast and fully, I was surprised. The descriptions of his world gave me insight that made me really feel what he was going through. I felt that I understood his anxiety and his confusion as his story unfolded. Mark Haddon does an amazing job creating a bond between his readers and Christopher.

If you know anyone with Aspberger's, I recommend you read this book. If you don't know anyone with Aspberger's, I recommend this book even more. I am so glad Ms. Roman is using this novel in her class because it will share a new perspective of the world with students who are unfamiliar with the kinds of feelings and challenges kids like Christopher face.

A few selected quotes from the novel, to give you a taste of Haddon's style:

“On the fifth day, which was a Sunday, it rained very hard. I like it when it rains hard. It sounds like white noise everywhere, which is like silence but not empty.”

“A lie is when you say something happened which didn't happen. But there is only ever one thing which happened at a particular time and a particular place. And there are an infinite number of things which didn't happen at that time and that place. And if I think about something which didn't happen I start thinking about all the other things which didn't happen.

For example, this morning for breakfast I had Ready Brek and some hot raspberry milkshake. But if I say that I actually had Shreddies and a mug of tea I start thinking about Coco-Pops and lemonade and Porridge and Dr Pepper and how I wasn't eating my breakfast in Egypt and there wasn't a rhinoceros in the room and Father wasn't wearing a diving suit and so on and even writing this makes me feel shaky and scared, like I do when I'm standing on the top of a very tall building and there are thousands of houses and cars and people below me and my head is so full of all these things that I'm afraid that I'm going to forget to stand up straight and hang onto the rail and I'm going to fall over and be killed.

This is another reason why I don't like proper novels, because they are lies about things which didn't happen and they make me feel shaky and scared.

And this is why everything I have written here is true.”

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Teaching Strategies for Comprehension

Chapter four of Kylene Beers’ book, When Kids Can’t Read: What Teachers Can Do, discusses the emphasis of teaching reading strategies over straight comprehension – and WHY it’s important. As a teacher-in-training, tips and guidance like Beers gives is as good as gold.

I have always been aware that as English teachers, we must teach and not just tell. Beers makes the distinction between instruction vs. instructions. There is a massive chasm between giving students instructions, which are only directions as to what to do, and providing them with instruction – teaching them how to do something. This differentiation will help me to really think about everything I am saying to my students. Reading the transcripts from the student teacher as well as the follow-up conversations really exemplified the difference between helping students with comprehension of a single text and helping students learn strategies that will help them understand texts they’ll read in the future.

In this chapter, Beers emphasized the importance of both modeling and discussion in the classroom. It is clear that for students to learn and be able to use new reading strategies, they must be clearly explained and modeled, then practiced. For me, this means that my classroom will be a combination of the guided practice method of instruction and student-centered. I will explain what strategy students are to focus on and HOW IT WILL HELP THEM WITH COMPREHENSION before I model it for them while reading aloud. I plan on using small group discussions and literature circles in my classroom so students will have the opportunity to model for one another, discuss their strategies and share unique perspectives on what they read. Beers makes it clear that students must be guided through the process of learning how to use comprehension strategies – sometimes more overtly than teachers may realize.

What Beers’ chapter helped me understand the most is the importance and power of reflection as a teacher. Through the inclusion of the transcripts with Kate, the student teacher, she modeled for me how much reflecting on lessons and instructional methods can help to improve teaching. Sometimes, because the program at UNH is so intensive and immersive, I feel as though I am expected to come out knowing exactly what to do for every class. Reading stories about teachers doing things poorly in their first few years of teaching is encouraging to me. It’s reassuring to know that nobody is perfect and mistakes will be made. The most important part of being a beginning teacher and making mistakes in the classroom is that I reflect! Mistakes can be a good thing, as long as they are used to improve lessons and methods for the future. I also believe in (nearly) full disclosure with my students. If I realize I have done something wrong or wish I taught something another way, I plan on sharing that realization with them – especially if I feel that they can immediately benefit. (Also, as a learning teacher, I like to listen to advice from students. Sometimes what they say is bogus, but it can often be intuitive.) For example, the first “discussion” that Kate had with her class about Eleven was more explanation on her part than students learning any strategies. Should I find myself in that position and had the benefit of debriefing with a mentor teacher, I would revisit the story with the same class. Discussing it again, with a different or more directed focus, would benefit both myself and the students.

Chapter 4 helped me to be more comfortable in my own "beginning teacher skin" – now I know it really is okay to make plenty of mistakes, because teaching is continuously learning -- right alongside the students.

Labels:

Beers,

comprehension,

instruction,

learning,

mistakes,

teaching

Location:

220 Coe Ave, Meriden, CT 06451, USA

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Ways to Create a Culture of Reading

Encouraging students to become avid readers and working towards creating a culture of reading in the classroom seems as though it is one of the most obviously important jobs an English teacher has. Unfortunately, I have seen teachers completely discourage students from reading -- not intentionally, of course. But not listening to what they have to say about what they read or by making reading a strictly individual assignment will turn many students away from the entire process of reading.

When I think about encouraging my future students to read for enjoyment and to see the benefits of reading, there are too many ideas that seem to come to mind. And, for me, that's exactly as it should be -- creating a culture of reading within a classroom means doing lots and lots of little (and different) things to get students involved in reading. Although every student may never get as excited as I get to see my favorite author at a book signing (although some might!) there are lots of things that can be done in the classroom to encourage them to read:

- Know what they're reading! (And what they want to read, but just don't know it yet.) In other words, as a teacher it is beyond important to be aware of the world of adolescent literature. Teachers need to be familiar with what the students are already reading and talking about. A knowledge base of adolescent literature will not only give the teacher insight into student interests, but also provide an opportunity to get more students reading. One of the best feelings as a teacher is choosing a book for a student with that "hunch" that he/she will like it and then finding out he/she loved it and is reading the next in the series or another by the same author.

- The American Library Association has an entire sector devoted to young adult literature: Young Adult Library Services Association. On their site you'll find titles, authors, awards and lots of ideas.

- Keep the classroom stocked. This seems obvious, but English teachers must have books in their classroom! When I have a classroom of my own I plan on keeping not only the classics that we read and the textbook in my room, but a wide range of genres and reading levels. I'll treat my collection like a rudimentary, mini library; students will be able to sign books out if they want to take one home. I may have students who do not have books readily available to them, as I always did when I was young. My students will know that if they are interested in a book I will do what I can to make it available.

- Make reading rewarding. Ideally, my future classroom will have the space for a "reading corner" where students can relax with a book. This space would be used only for students who are reading and as a kind of reward -- which would vary from student to student. Maybe for a student with a behavioral plan who was able to focus all period or for a student who made honor roll for the first time. Hopefully this would help students to see reading as something positive and a valuable way to spend their time.

| |

| Although somewhat ridiculous and very elementary, this was the most obvious example. | You get the point... |

- Make reading social. There are too many teachers who see reading as a quiet and individualized assignment. Students need to be able to discuss what they are reading with one another -- whether that means they're all talking about different books they read on their own or a text for class. In my future classroom I'd like literature circles will be used at least once a week. Each member of a literature circle group will have a different task, such as summarizer, artist or discussion director, and the students will get a chance to discuss what they read on a more intimate level with one another. These literature circles will also encourage students to think about a text more critically and on a deeper level.

- Go beyond the text. Go ahead and scoff, but sometimes the movie really was better. Because I have a background in film, I would love to be able to read a book, watch the film, and then discuss the two with my students. Comparing a text to its film adaptation is one of my favorite things to discuss and hope to share that with students. When students see that so many films are based off novels or short stories, their interest will -- hopefully -- be peaked and they will motivated to read the book that inspired their favorite movie.

And just for fun...

Sunday, January 8, 2012

Struggling For Independent Reading

Students often struggle not only with reading, but with simply picking up a book. Beers’ chapter two, “Creating Independent Readers,” of her book When Kids Can’t Read relates directly to what I often do in my internship at Platt High School. At least three days out of the regular school week I work in the Read 180 classroom. Read 180 is a program for students whose reading skills are below (often times far below) what they should be at the high school level.

Beers wrote about the difference between dependent readers and independent readers. Independent readers have an arsenal of various strategies they can use in order to help them get through a text, such as: “recognize the author’s purpose, see biases, note an unreliable narrator, find the antecedents needed to navigate a maze of confusing characters, or make connections to [one’s] own life” (Beers 15). In contrast, dependent readers may be able to get through a text but their comprehension is only at surface level and their strategies include asking the teacher to help them or even tell them.

The most important distinction Beers makes about reading is that teaching dependent readers doesn’t mean teaching them how to immediately understand what they read, but “how to struggle with a text” (16). I see so many students in Read 180 who don’t have the patience to stick with one book and because they don’t have the skill set to know how to handle the book, they quickly give up. These students need to become readers by learning skills which will lead to comprehension.

The first thing most of the Read 180 students need is confidence. Many of the students tell me that just being in that class makes them feel dumb and always ask for me to close the door so no one will see them. Beers separates confidence into three separate sections: Cognitive confidence (comprehension), social and emotional confidence (willing participation), and text confidence (stamina and interest) (18). Without the belief they can succeed, the Read 180 students – and dependent readers everywhere – will fail to achieve that confidence and eventually become strong, independent readers.

---

Beers, G. Kylene. "Creating Independent Readers." When Kids Can't Read, What Teachers Can Do: A Guide for Teachers, 6-12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003. 8-22. Print.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)